The City in the Time of Coronavirus

The City in the Time of Coronavirus

‘Wisdom comes to us when it can no longer do any good.’

Love in the Time of Cholera, Gabriel Garcia Marquez

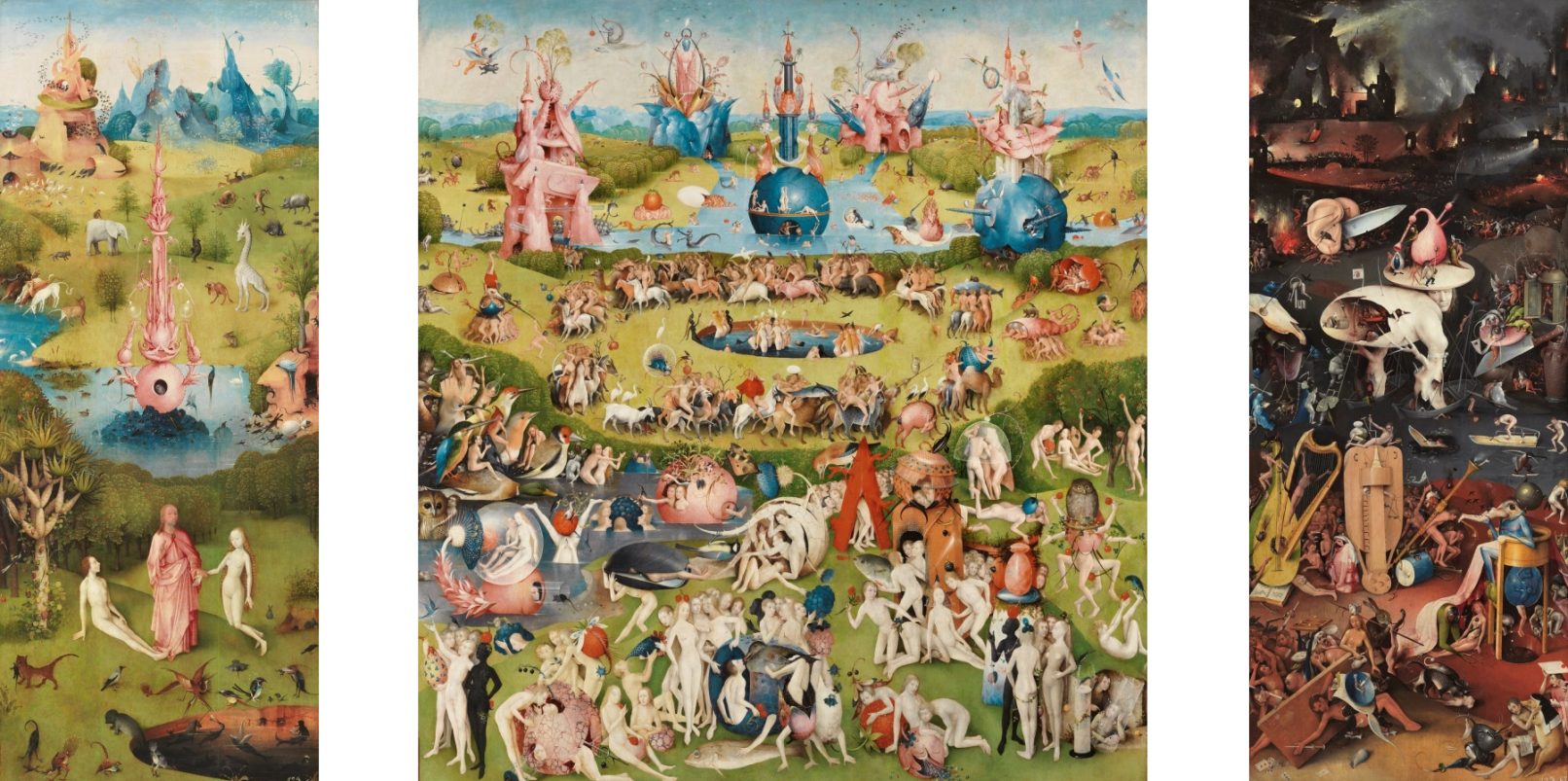

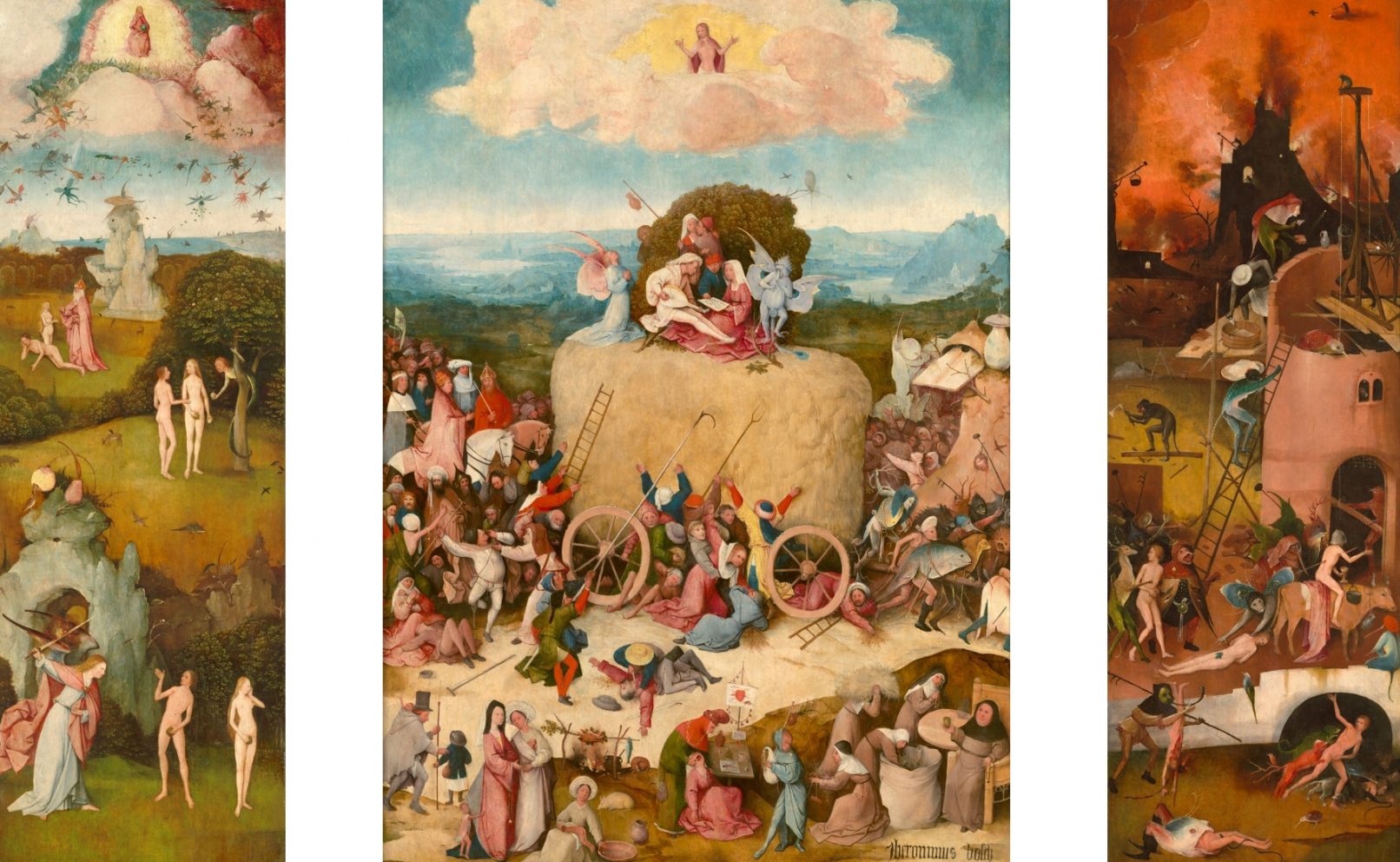

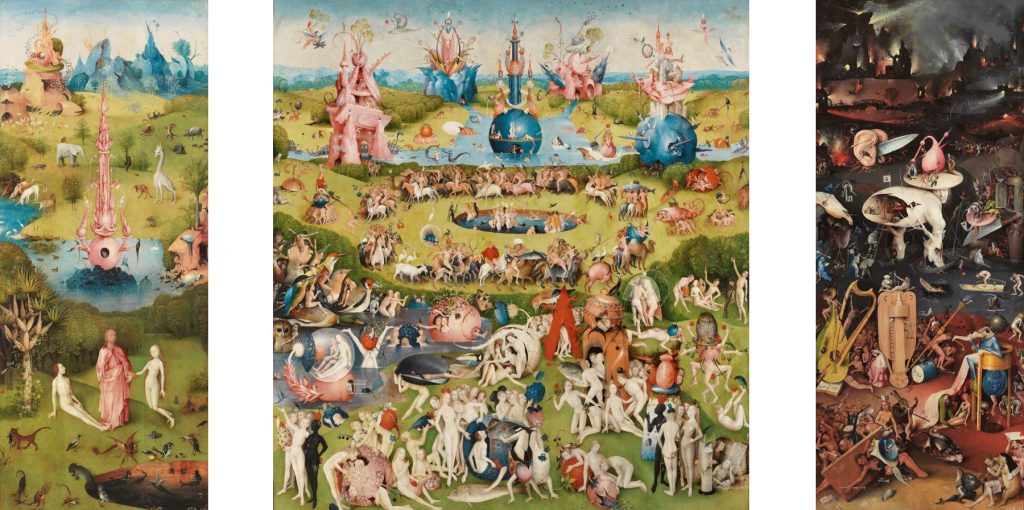

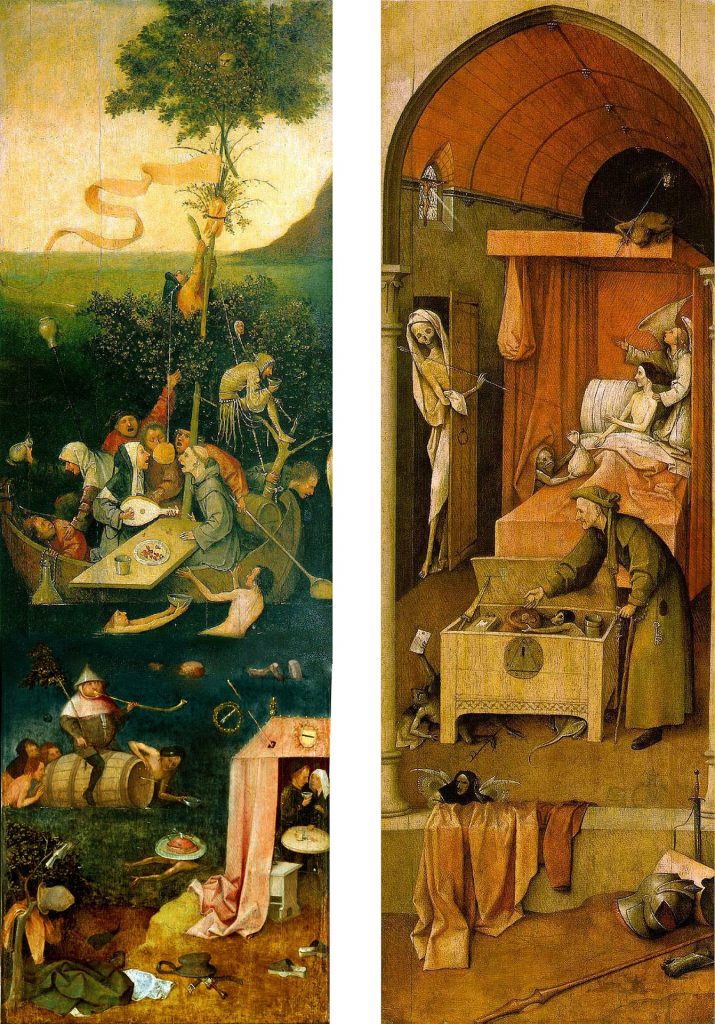

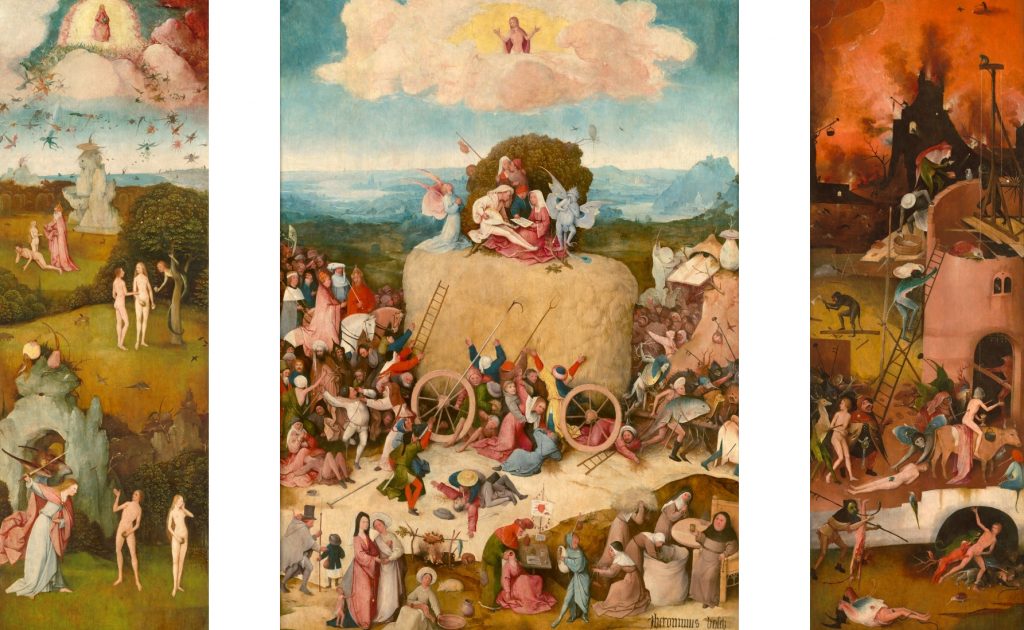

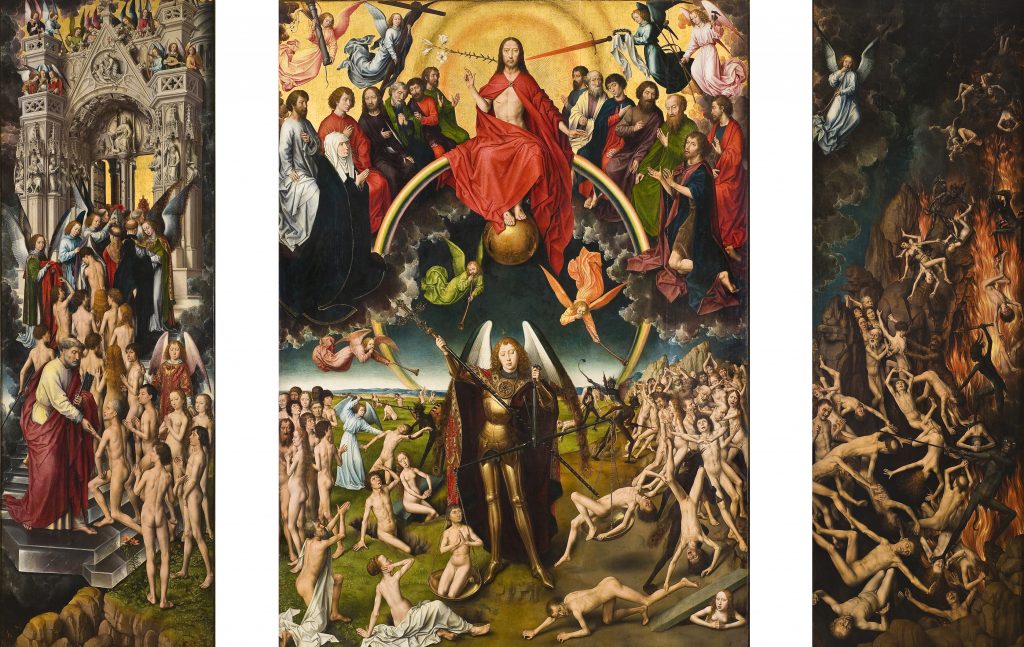

Dante Alighieri, the Italian poet, concluded that sins are in some form or another a corrupt version of love. While he was writing his Inferno sometime before 1317, he used a long-lost list of seven capital sins compiled by late fourth-century theologians as the structure of the levels of purgatory. In his book, the Italian linguist described and transcended those levels to reach paradise. Since, this set of vices -and their correlating virtues- has inspired altarpieces, paintings and novels throughout western tradition, as a reminder of the horrors of human mischief and excess and the ways to outdo them.

The Coronavirus epidemic, as one of the plagues of old, feels like one of these landmark moments in history, when bashed humanity remembers its lost virtues, drawing on one of the traits that most distinctively makes us human, the ability to gather strength and positivity from moments of despair and uncertainty.

Lust (luxuria) / Chastity (castitas)

Humans concentrate very densely in particular points of the globe. Human settlements and infrastructure take only 1% of the habitable land of the Earth.[1]

Closer to home, as of 2016, only 6.8% of British land is considered urban, accounting for less territory than the shore revealed when the tide is at its lowest. Those scattered and dense concentration points are cities. In the case of the UK, 81.5% of the country’s population reside in these limited spaces.[2] Anyone that has been stuck in a traffic jam, crowded in the London underground during commute or queued for hours for a restaurant table will surely wonder what all the fuss about proximity is between humans.

Nevertheless, major conurbations like London still are a desideratum for visitors. A constant injection of young, vital workers seeking new market opportunities land in the city daily. At the time of the 2011 census, 38% of the workforce in the city was foreign and generally more skilled than UK-nationals.[3]

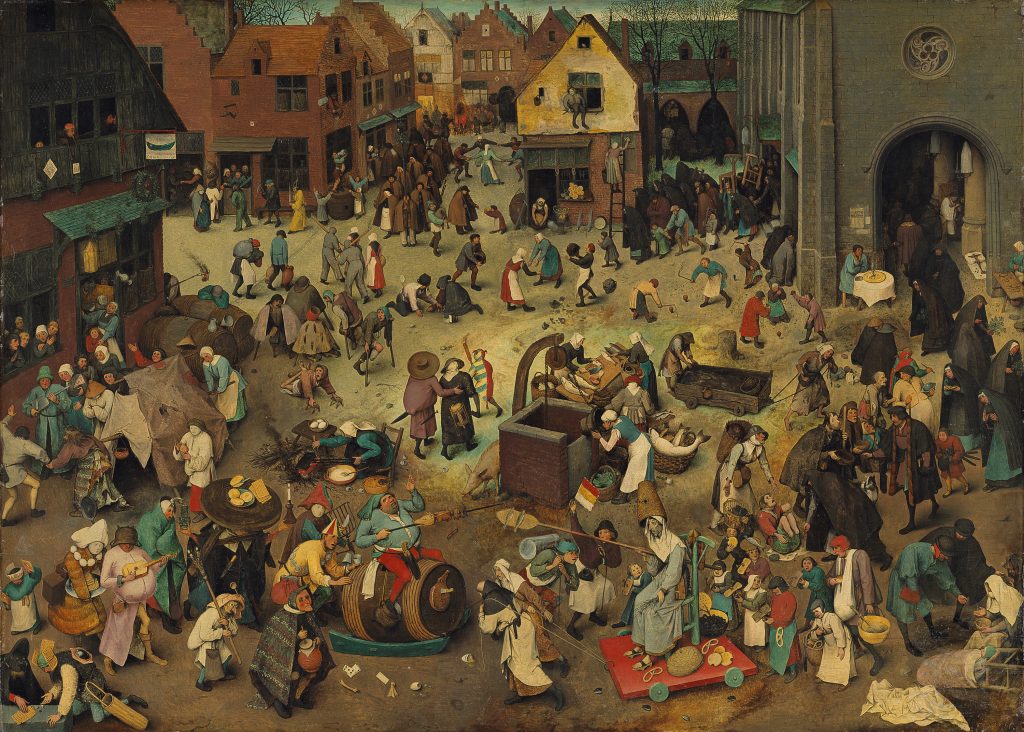

The agglomeration effect is visible all around. Cities attract young, creative and adventurous individuals. In the EC1V postcode alone-the area around the Old Street roundabout- 32,000 new media and ICT businesses have flourished in the last two years. Together with them, fair-trade coffee shops, pop-up fashion stores, independent art galleries and bicycle repair stores have also sprung, catering for the LUST of the new Flat White class, in a perfect case-study of scale and agglomeration economy. [4]

With a very simple economic model relating inputs and outputs to the perimeter and the area of a city respectively, Brendan O’Flaherty proves how, when cities grow over a certain size, they can do more with less, giving a theoretical answer to the question, should I be moving with my cat and my cafetière to Hackney.[5] Millennials pack in tiny flat-shares in Hackney, Islington and, to a lesser extent, in Haringey, painstakingly trading the lack of domestic space for the captivating work & play lifestyle of these vibrant hotspots. The traditional Westminster clean-shaven high-earning banker way of life has now been outgrown by the agglomeration of East-end moustaches and fixies, flocking around the latest pop-up sneaker store near Spitalfields Market.

With the irruption of the Coronavirus, these lustful effects of congestion might be at stake. Many of my British friends and colleagues have run to the hills during lock-down to fill their family houses in the countryside, many of whom pledging to never return. They are finding social distancing much easier, and they are forgetting at once the externalities of the congested city. No more traffic jams, noise and pollution to get to work, at least whilst internet connectivity holds.

Still, the glowing neon and concupiscence of the leisure and lifestyle offer of the city will likely keep the younger and groovier strata of society in London, together with the choiceless have-nots. But, could this be the time when hordes of tech-savvy, middle-aged, white-collar (and white-skinned) professionals will flock with their youngsters to the motherland beyond the green-belt? How far from London will they venture and what will be the real estate like? Will it be closer to a Villa Urbana, a country seat that could easily be reached from Rome during the Republic and Roman Empire, or to a Villa Rustica, the remote farmhouse estate permanently occupied by the servants that took care of it?

If the latter is the case, will the British countryside be up for grabs when this wealthy city class crosses the fences? County farms are the legacy of an era of land reform, when Joseph Chamberlain and other Victorian politicians campaigned for cash-poor tenant farmers to be lent ‘three acres and a cow’ at the beginning of the 20th century. Yet, the extent of England’s County Farms has halved since the 1970s.[6]

What will the social and economic repercussions of this Covid-19-infested land-value rising vector be after landing on these appealing properties and on the rural land in general across the subsidy-dependent farming communities of the UK? Will farmers and farms be ready?

Greed (avaritia) / Charity (caritas)

Cities are pits of global investment. Setting aside the technicality that all UK land ultimately belongs to the Crown, traditional landowners in the UK have been bleeding land to foreign investments. In London, some of the largest estates have seen their property stock halved in less than 100 years. The Cadogan Estate has moved from 200 acres of property in 1925 to barely 93 in 2017. Same with the Grosvenor Estate -in the hands of the Duke of Westminster- or the Howard de Walden, the Duke of Bedford or the Marquess of Northampton Estates, owning hundreds of acres of property at the beginning of the century, see their domains shrunk in the ranges of 20 and 30 acres today.[7]

These days, investors from all over the world rub shoulders with the traditional London Estates, public sector bodies and big developers in the prestigious locations of Kensington, Knightsbridge, Mayfair, the City and Canary Wharf. As an example, the government of Qatar, a tiny country of 2.5 million people with an extension of roughly the size of Yorkshire, has tapped into some of London’s most iconic developments. Qatari Diar owns the former US Embassy in Grosvenor Square and the Quatari Investment Authority owns the Chelsea Barracks site, the Olympic Village, The Shard and some of the City’s tallest skyscrapers.

These dense, high-rise developments are justified by several planning instruments in London, and most clearly by a measure well-known by architects, urbanists, transport planners and investors alike, the PTAL. The Public Transport Accessibility Level is a measure of connectivity by public transport provided by Transport for London. It maps the city and its connectivity levels. For any selected place, the PTAL suggests how well that location is connected to public transport, how close it is to tube and rail stations. The London Plan directly links housing density to these guiding levels, in a logical argument to build higher and denser where the connection is better, constituting the base for transport-led development.[8]

This mutual arrangement, by the second and third largest landowners in London, the Mayor and TFL respectively, works well in an established city, and opens the possibility of relatively low-risk investment on the mega-developments that the planning system permits in high level PTAL areas. “In Qatar they can get a 50% or 60% return against 5% or 6% here in the UK,” Raed Hanna, of Mutual Finance, says. “Nevertheless, the UK (and London) is still considered much safer than their own country, where they are too politically exposed.”

However, the global capital GREED has also ventured into the wilderness. Global cities are secure places where many players want to baccarat, and the tables are already getting filled. The democratization of air travel and cheaper credits opens the opportunity of bringing the logic of transport-led development into the realm of air traffic. Crafty developers now back the viability of their real estate investment on purposely built airports in remoter locations with a more benign legislative climate. Most of them remain empty to this day.

Can you think of a less desirable place to live than under the flight path of a cargo plane, carrying future-to-be iPhone chemical components instead of humans, because no-one wants to visit the recently inaugurated green-roofed third-tier designer outlet in your desert-ed city?

Even if governments have been reluctant to restrict domestic air travel, Coronavirus is impacting global air traffic. Could this deceleration shake the justification behind some of this vulture investment that builds nowhere for no one?

It is interesting to note the impact of local capital on other local capital, in this case mediated via air connectivity. Tourism and their tourist-targeted communities have also blossomed after the race for cheaper flight fares. No longer leather seats on flights, the reduction in cabin leg-room has also resulted in a parallel trim in ticket prices. Advertised prices from London to New York (one-way) have plummeted from a life-earning expense of £5,412 pounds in 1955 to a budget-friendly £233 in 2018. All within one year, hordes of tourists head to a summer booze-holiday in Spain, winter holiday in St.Moritz, Easter Break in Mallorca and autumn escapade to the Cyclades. Overall cost of flights? Way below the average monthly net salary of £1,730 in the UK.[9]

The influx of this cash-ready travelling class has resulted in some of the most outrageous developments along the Mediterranean coast. This is the case of the Urbanizaciones Riviera del Sol y Miraflores on the Andalusian Costa del Sol. Initially a seasonal tourist destination, they are now a permanent site of international retirement migration. This water-thirsty region of 1,382 sqm land contains 60+ gold courses catering for a foreign population that ranges from 250,000 to 600,000 out of the 1,252,872 registered residents. Britons are the majority.[10]

The explosive growth of these areas can be traced back directly to the exhilarating air travel cost. What will be the consequences of the halt of global air traffic, after the current Coronavirus epidemic, on these and more vulnerable holiday communities? What will be the impact of the tourist destination craze? How will sunny retirement communities reinvent with less flights, and potentially less young-old customers?

And more importantly, where will real estate investment set its radars on in the times of a global transport slow down?

Gluttony (gula) / Temperance (moderatio)

To thrive, the pandemic-induced remote workforce must rely heavily on ICT in Coronavirus times, to be sure. The irruption of the disease is already changing the way we work. It is likely that flexible working hours and locations will become more common on the near horizon to encourage social distancing.

Simultaneously, the relevance of ICT capability grows even bigger outside of the professional sphere, as the only means to overcome the current solitude of the living room, if you are lucky to have one. New technological platforms are flourishing. Just like Google and Uber are now verbs, so is Zoom. Accordingly, first-time installations of Zoom’s mobile app have sky-rocketed by an outstanding 728% since March 2, 2020.[11]

Since the advent of the Nordic Mobile Telephone in 1982, the first 1G mobile system, a new mobile generation has been renewed every ten years. In April 2008, NASA and other partners set to develop the next stage of this communication technology. This next phase of mobile network, the 5G generation, is rolling out in these Coronavirus times, and pledges for much faster data download and upload speeds, wider coverage, and more stable connections. For software companies, the challenge used to be which design applications could fully take advantage of this enormous capacity.

Coronavirus might be the answer to the quest for the killer app, as 5G treats and virtual/augmented reality are inextricably intertwined. Apps that could make Zoom pale in comparison might be around the corner. Facebook Horizon, the last in a long string of investments on social VR, might be a timely COVID-proof virtual platform.

The City, no longer relevant as a realm of social interaction, could be dismantled before our eyes in the reflection of a led screen or a pair of Oculus glasses.

A more concrete reality, however, is the inevitable loss of jobs that the lock-down will result in. Close to one million people in the United Kingdom applied for benefits in the last two weeks of March. In Britain, the surge in universal credit applications followed government measures to limit the spread of the virus, including closing pubs, restaurants and non-essential shops. Many of those small and medium businesses will never re-open.

In the aftermath of this tragedy, Amazon’s surge in demand has driven the business to near peak holiday season levels. To keep up with the increasing customer pressure, the company plans to hire 100,000 new workers, and Jeff Bezos, who still owns 11% of the company, is now the richest person in the world. In COVID season, we have already forgotten the corner shop, and we are just slightly annoyed that our Amazon-prime subscription’s ETA has gone up by a couple of days.[12]

Pre-disease, the UK was already a great growing field for online retailers, as internet shopping already accounted for 23% of the sector in 2016. Per capita, Britain had the largest online-purchasing population in the world, by more than 10% over the next country, Germany.[13] The proud British high-street was already a place of monoculture, the consequences of the lock-down forcing more and more small businesses to pull the plug. In a very compartmented and polarized urbanism such as the British, where only a handful of streets are planned with ground floor commercial uses and the ‘defensive space’ is sacred, the cities are likely to become grimmer and more homogeneous when people hit the streets.

Another stress effect might be on the obsolete typology of the shopping centre. Temples of the Latter Days Saints of Consumerism, their unsanitary conditions make them a fit typology to re-think. Already declining in the UK, they are still an unfulfilled wish in booming consumerist economies in the developing south. Maybe they still have the chance to add some windows and green make-up to the type. Sadly, they might become even more appealing.

Meanwhile, under social distancing times, as customers turn to online delivery services out of fear of the plague, Amazon has the possibility of transcending its current outreach, becoming a global utility provider. In a big data world, the companies that gather the largest datasets are the ones that dominate the market, the more you consume, the more they know about you. Their finely-tuned AI algorithms can predict consumer behaviours and target their marketing strategies accordingly.

By the end of the COVID stalemate, their GLUTTONY will surely have eaten most contenders, and customers will virtually march to the smell of honey.

Sloth (acedia) / Diligence (industria)

In The Fear of Freedom, Erich Fromm[14] explains how for a large portion of the western tradition, the individual did not exist as such. During the medieval period man was bonded to the feudal structure and the church, working the lands of those in power, that barely yielded any profit. Accumulation was selfish and suspicious. Private property was a just a concession to the frail nature of the human, a sort of collective communism was the ideal.

By the end of the 15th century, guilds became larger, some master craftsmen started to employ more and more men. Modern capitalism started to develop, in a process of individualization that made the German medieval expression ‘Stadtluft macht frei’ (the air of the city makes you free) very real. Trading cities blossomed and, in exceptional cases like Venice, Genoa or Lübeck, cities themselves became powerful states, sometimes taking surrounding areas under their control or establishing extensive maritime empires.

Fast forward into the early 19th century, the mercantilists empires of the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, French and British had expanded Europe’s larger capitals -in both the monetary and urban meanings of the term- on Atlantic trade. In the individualizing capitalist process, efficiency starts to be a central moral virtue. A new rising feeling of freedom and independence separates the individual from nature and the collective.

The free individual is also a fearful one. Freedom is not an experience we enjoy. Fromm suggests that many people, rather than embracing it successfully, attempt to minimise its negative effects by developing behaviours -namely masochistic and sadistic- that provide some form of security. That is the mechanism that explains why the advanced society of Germany of the 1930s was so willing to give away their freedom to Nazism.

More dangerous is the third mechanism that Fromm’s suggests to bypass individual responsibility and ease the fear of freedom: conformity. The SLOTH in adhering to the normative belief systems in place in society is just another way to cure anxiety-filled free-thinking.

In exceptionally stressful times, these narratives are key for fear levels to be kept high, and we know that in the light of two events that hit the US in recent years. [15] In 1995, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols bombed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, killing 168 people. It was the largest terrorist attack on American territory at the time. A few days later, polls asked Americans: How worried are you that you or someone in your family will become a victim of terrorism? More than 40% said they were very worried or somewhat worried. However, over the next few years without another mass bombing, that number dropped steadily.

Six years later, the September 11th attacks raised that percentage to 58%. After a month, it was back to 40% again. It looked like fear would continue to dissipate. Instead, those levels never decreased lower than that figure. So, even after US troops killed Osama bin Laden, Americans returned to believing that the government wasn’t doing enough to prevent further terror attacks.

One of the differences from the Oklahoma and the September 11th attacks is the strong narrative that was developed after the second. Casting aside the implicit us vs them dichotomy, as hard-wired in human biology as the main broadcasting companies in the west display, a constant feeling of threat impedes a clear vision of reality. In the US, the Patriot act, signed as law only a month after the attack, authorized of indefinite detentions of immigrants, granted permission to search a home or business without the owner’s or the occupant’s consent or knowledge and allowed the FBI to access any citizen’s telephone, e-mail, and financial records without a court order.

The times of the Coronavirus lock-down, when the whole globe is finally scared at once, are dangerous times for careful thinking. The epidemic has brought fear into our cities, and some new fears are already being packaged into the new-normal narrative. Fears of contagion may lead us to become more conformist and tribalistic. Our moral judgements become harsher and our social attitudes more conservative when considering issues such as immigration or sexual freedom and equality.

Be careful with the promise of efficiency and safety that comes with the pandemic, we might be giving away more than our battered freedoms. When AIs understand our desires and our biology better than ourselves, who will contest their measures? At the moment of writing this text, my friends and family in Spain haven’t seen the light of day under lock-down, while I am enjoying global warming in London, going on sunny rides on my carbon-fibre road bike around the post-apocalyptic city centre, and people in Sweden have the only restriction of not gathering in groups larger than 50 people. Even if politicians elude their responsibility by showing the my-friends-is-an-epidemiologist-and-he-knows-better card, lock-down measures feel sloppy and improvised, still a human construct.

But who will have the capacity to question the decision-making capabilities of an algorithm in the aftermath of the pandemic, one that reads the city and monitors the biology and psyche of its citizens and understands their very human difficulty with freedom better than they do?

Envy (invidia) / Gratitude (gratia)

In the mist of the pestilence, the richer 10% of the households in Britain have over a hundred times more wealth than the poorest 10%. Regardless who you are, you are counting on housing as your only way to climb up the ladder.[16]

By 1995, the median 50-year-old in London had a net wealth of £66,000. Thanks to the housing boom, that figure rose to £187,000 by 2005. Everybody was thrilled, assets skyrocketed. It was relatively easy to grab onto the wagon. After the 2008 global housing crisis, parents are thankful they were quick enough and can help -sort of- with their kid’s first deposit today.[17]

By 2013, the average starting deposit for a house in London was £64,000, while the ratio of median house price to median gross earning per household in London increased from 6.9 in 2002 to 12.77 in 2019. Even that first deposit feels like an unsurmountable obstacle for most households. The lower quartile of property prices in London starts at £355,000, and that’s the only quartile the ONS has on their website. Even the bank of mum and dad would need to break the piggy bank with these ‘cheap’ ones.

With an average net family wealth of £50,000 in 2016, millennials (19 to 38 years old) can barely afford to even put down a deposit on their first home. On the flipside, they are the lucky ones. Rough-sleeping figures in London hit a record high, with 8,855 people recorded as bedding down on the capital’s street in the 2018-19 period. Simultaneously, close to half of the U.K.’s billionaires call London home. London is the fourth wealthiest city in the world after New York, Tokyo and homeless-infested San Francisco. [18]

Social rank, namely your relative position within the hierarchy, and not your material wealth per se, has proven adverse adrenocortical, cardiovascular, reproductive, immunological, and neurobiological consequences in humans. As real as a COVID infection, it is the realization of inequality that sickens. If you are a young professional living in a 10sqm room within a 4-people flat share overlooking Battersea Gardens in the luxurious Nine Elm Development, that is a constant reminder of your position in the socio-economic hierarchy. Even more flagrant if you are rough-sleeping in Victoria Station begging for money to a Sloane Square resident going for a walk to Hyde Park. No wonder you feel stressed. ENVY is a consequence of inequality.

And now we are constantly reminded. The coronavirus lock-down has made us feel unworthy. No need to walk the empty Belgravia Mansions on our allowed one form of exercise a day. We have seen the rich and famous in full colour in our smartphone screens. Madonna’s Instagram post, claiming ‘COVID-19 doesn’t care about how rich you are, It’s the great equaliser’, makes it all that much ironic.

In a country where the only public housing investment that has expanded in the last decades is prisons and politicians claim they don’t know how many homes they own (D. Cameron, 2009), the COVID-19 could be the call that…

Wrath (ira) / Patience (patientia)

…wakes citizens up in WRATH. There are 22,000 empty homes in London alone. Most in the richest areas of the city: Knightsbridge, Belgravia, Mayfair, Kensington and Westminster.[19]

Angry citizens, in their crowded coops, keep listening to the government, to housing charities, to housebuilders loudly proclaiming: we are not building enough houses in the UK! The popular story repeats that the rate of home building is so slow that house prices have rocketed. The story, though, sounds more like a fantasy when now we have more housing in Britain – more homes and more rooms in those homes than ever before. Not just in absolute terms, but per family and per person. However, those homes remain close.

Problem is, since Thatcher and the Right-to-Buy, the public sector has deregulated the housing market. City of London and the Boroughs, amongst the biggest landowners in London, rely on the private sector to develop their land while taking a portion of the consequent raised value. They have a big interest in letting developers wait to start building so their land gets fat until selling prices are at their peak. They also enjoy the benefits of soaring selling prices when the homes are built. Both strategies translate in a bigger share of the pie for the authorities.

No surprise then, when affordability is so ill-defined. No surprise when the London Plan has already scrapped its pyrrhic requirements on room and dwelling sizes and now contains no requirements on the matter whatsoever. Barely an eyebrow rises when, in the last decade, London has lost 8,000 social-rented homes and crushed council estates are replaced with less and less affordable housing in high-end developments.[20]

Large developers know many tricks to avoid matching the affordable figures -which are not overtly ambitious- set by the Boroughs. And they are acquiescently accepted. Rather than going into much more detail, the bottom-line is don’t ask what your Borough can do for you, because they won’t.

I wonder if this time of the Coronavirus might make citizens realize that they need to take matters into their own hands if they want to level the housing conditions up. Housing cooperatives, that join similarly minded citizens into building their own homes without much public or private intervention might become attractive alternatives for the abused middle class. They might appreciate the financing possibilities of co-housing and self-building, where the exclusive facilities and spacious interior spaces of higher-end dwellings are made affordable by sharing costs.

As for the have-nots, there are still 22,000 empty homes in London…

Pride (superbia) / Humility

The population of Homo Sapiens has been more or less stable for the past 200,000 years. In the last 200 years of our history, however, our population has sky-rocketed from 1 billion in 1800 to around 8 billion in 2020. And this trend is likely to continue. In just a little over 200 years we have managed to bring the environment to a halt and populated the Earth with either us or our products.[21]

Our PRIDE tells us that we will be able to undo the effects of industrialization and consumption with more industrialization -this time wind, solar, or biomass production- and consumption- this time vegan, healthy, macrobiotic, sustainably-sourced, you name it. We are already using 50% of the habitable land on Earth just to feed ourselves.[22] In the meantime, we have filled the world with 1.5 million cows and 23.7 billion chickens. Overfishing is rampant and stopping it has proven to be very hard. And with 10 billion humans walking the Earth by 2050, what will the consequences be?

Has any species before us voluntarily limited their growth in a conscious and democratic collective effort?

Even if wars have grown more frequent in the last centuries, the rise in population counteracts their effect as a way of limiting booming growth. In Europe, the last major war ended more than 70 years ago. And indeed, our population is growing old happier than ever before. In the western and westernized world, we are now smart enough to make ourselves sick from lifestyle-related diseases and diseases of old age.[23] Meanwhile, the poorer and more congested countries in Africa -Niger, Angola, Congo among others- are growing at an unprecedented rate. In the struggle against natural calamities, the scale is tipping in humankind’s favour, the old in the north and the poor in the south are growing in number. [24]

Has God sent this plague to save humanity from its sins? Or, out of unconditional love, have we prayed to Google just enough to be purified?

‘The only regret I will have in dying is if it is not for love.’

Love in the Time of Cholera, Gabriel Garcia Marquez